The Right to Read Anonymously

In 1996, in the Connecticut Law Review, legal scholar Julie Cohen wrote what has become a landmark article in Internet Law entitled, "A Right to Read Anonymously: A Closer Look at "Copyright Management" In Cyberspace." She began by stating,

A fundamental assumption underlying our discourse about the activities of reading, thinking, and speech is that individuals in our society are guaranteed the freedom to form their thoughts and opinions in privacy, free from intrusive oversight by governmental or private entities.

Cohen notes that, in the past, our right to read anonymously has been protected by libraries and librarians. See, for example, the American Library Association's Freedom to Read statement, adopted in 1953. Our American experience has generally been that one is able to walk into a public library, take almost any book off the shelf, sit down, and read without ever identifying oneself or asking anyone's permission. Most libraries, as vigorous defenders of reader privacy, only maintain information about which books you check out until you return them and then they destroy any record connecting your identity to the books checked out. It was, in 1996, the growing prevalence of electronic dissemination of information and technologies to monitor our receipt of such information that prompted Cohen's article and its special focus on those monitoring technologies.

Cohen explains the case law that has supported the right to read anonymously, typically predicated on "the likely chilling effect that exposure of a reader's tastes would have on expressive conduct, broadly understood -- not only speech itself, but also the information-gathering activities that precede speech." In Stanley v. Georgia, 394 U.S. 557 (1969), the Supreme Court recognized "the right to satisfy [one's] intellectual and emotional needs in the privacy of [one's] own home" and "the right to be free from state inquiry into the contents of [one's] library." Cohen also explains how the Supreme Court's jurisprudence on the right to speak anonymously and on associational anonymity, each more traditionally understood as protections provided by the First Amendment, also support the right to read anonymously. I believe her analysis is absolutely correct and that the First Amendment rights to speak and to associate are intertwined with this right to read anonymously such that we should see the right to read anonymously as a fundamental constitutional right.

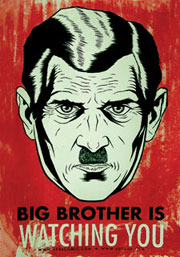

Now, imagine a different sort of "library," so different from traditional libraries we should instead call it simply a "repository." This repository has no shelves or books directly accessible to the public. Instead it has only a giant counter, guarded by something so unlike librarians, we must call them "sentinels." One must request every document one wishes to read from these robotic sentinels who will make fastidious notes about your every request. These records of your reading habits are maintained for at least three months and maybe longer. No one knows for sure.

Imagine further that before a sentinel will grant any of your document requests, one must provide the sentinel with one's full name, date of birth, full address, phone number, email address, and a credit card. The credit card is necessary, because every request you make of a sentinel incurs a charge, and most every document you are granted permission to view also costs money.

Now imagine further that this Orwellian repository is run by the government and that the documents it keeps under such close watch are all public domain court records. These documents are the very law itself. One's First Amendment right to read anonymously is thwarted by such a system, and this is precisely the system our own government operates right now under the name "PACER." PACER requires the above identifying information in order to establish an account and gain access and PACER's quarterly billing statements contain this detailed record of every document you read on PACER. The privacy policy at PACER.gov gives no indication how long these records of your reading habits are kept by the government. On this Constitution Day, I submit, that for this reason alone---ignoring many others---that the PACER system is unconstitutional and must be changed.